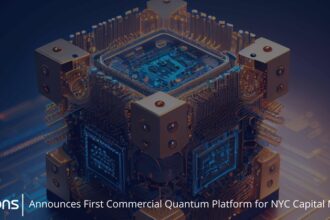

In 2025, IBM announced it expects quantum advantage by 2026 and revealed its quantum roadmap targeting a large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computer by 2029.

- IBM is predicting the quantum advantage in 2026. What will make this happen? Is it a breakthrough in hardware?

- How do you assemble teams that span physics, materials, and computer science?

- When it comes to practical applications, which areas do you see being impacted first?

- How do you see the convergence of AI, quantum, and HPC?

- There are a lot of theoretical problems yet to be solved, for example, P versus NP. Do you think quantum computing will be able to solve such problems?

- What will IBM Quantum be working on over the next few years?

In this interview, Oliver Dial, CTO of IBM Quantum, discusses what’s needed for quantum advantage to happen, and why the first big breakthroughs will probably be in chemistry.

IBM is predicting the quantum advantage in 2026. What will make this happen? Is it a breakthrough in hardware?

It’s really the convergence of three things. One is that the hardware is getting better. The main limitations to quantum hardware are the number of qubits and the error rate, because the error rates are quite high compared to classical computers. If the number of qubits is too small, it’s easy for a classical computer to simulate the hardware. If you can simulate my quantum algorithm on your phone, it’s probably not a quantum advantage.

Similarly, if the error rate is too high, there’s a different set of techniques you can use to model the hardware classically. Around 2023, the quantum hardware got both big enough and low enough in error rate to reach the point where you couldn’t simulate it directly using classical methods.

But you need to go a little beyond that, because the algorithms you want to use for advantage don’t map perfectly efficiently onto the hardware. There’s overhead. That leads to the second thing: algorithmic improvements. This includes finding algorithms where there’s the biggest possible difference between performance on quantum hardware and classical hardware. From that, you realise quantum advantage. It’s really a scientific question. You’re not looking at algorithms that are directly useful in a business sense; you’re looking for places where you can show separation. There have also been advances in the algorithms, in the ways that we operate the quantum hardware so that we can get more accurate answers out of the same hardware.

When you put all this together, there are two general things that need to happen to get to quantum advantage. One is continuing to improve the infrastructure. The other is having clients and partners who are experts in applications and algorithms to use the hardware to demonstrate advantage.

There’s a third element as well. Advantage is defined as outperforming classical computing, so you also need an expert in classical simulation techniques. You need a head-to-head comparison between the best quantum techniques and the best classical techniques on the best possible infrastructure.

2025 was our rallying call: The hardware was good enough, and it was time to build these groups of algorithm experts and hardware teams and push towards an advantage. We’re already seeing academic publications edging up to that point. I’m more optimistic than ever; it may be early in 2026.

How do you assemble teams that span physics, materials, and computer science?

At MIT, I was doing condensed matter physics experiments. And specifically, I was studying what electrons do at very low temperatures and very high magnetic fields. And so I sort of transitioned from that very basic research in the behavior of correlated electrons to spin qubits, and then came to IBM to work on superconducting qubits.

That’s why the IBM Quantum network is so important, because it’s really hard to assemble all the expertise that you need. And so we really focus on making available the infrastructure, the software, the hardware, and the platform on which people can run quantum computation.

We also partner with others who bring domain expertise in areas such as chemistry, material science, etc, together with algorithms. We participate in working groups, which are groups of academic and government researchers that are interested in particular areas such as healthcare, life sciences, optimisation, and material science. We also have Qiskit add-ons, which let people contribute implementations of their expertise so we can assemble complete workflows.

Trying to bring all of that expertise together under one roof would be like trying to put all the scientists in the world into a single lecture hall. It just doesn’t fit. It has to be a community effort.

When it comes to practical applications, which areas do you see being impacted first?

My personal guess is, the first impacts are going to be in chemistry and material science. Those problems map very efficiently onto quantum computers without very much overhead. It’s a fairly straightforward application. We’re already close to parity between quantum and classical simulations for simple molecules.

If you think about what the ages of man are named after, they’re named after our materials. We’ve got the Stone Age, the horizons and Copper Age, if we can start advancing materials discovery, that’s a huge impact.

Beyond that simulation aspect, a lot of the algorithms where people talk about advantage require circuits that are much wider and deeper, with much lower error rates and much bigger computers than we have today. That includes Shor’s algorithm and also some of the algorithms for optimization, such as simulating turbulent flow. These require large scale, fault tolerant quantum computers.

We think such quantum computers will be commercially viable in about four years, but even those probably won’t be big enough for Shor’s algorithm. The Starling system we’re coming out with in 2029 is going to be about 200 qubits, and we’re aiming for about 100 million operations. For Shor’s algorithm, people often talk about around 3,000 qubits and roughly 10¹² operations. That’s far beyond what’s on our roadmap today.

People also think there will be early quantum advantage in optimization and machine learning, which are, of course, very tightly linked. It’s a little controversial within the field, though, because the dominant techniques in those are all heuristic. We have problems that we know are hard. The traveling salesman problem is one that people bring up a lot. But there are classical algorithms, which are approximate heuristics, that are so good they might as well be perfect. It’s hard to prove why they work as well as they do. We are just beginning to enter into an era when we can start to explore quantum heuristic algorithms. You can’t really do it until you have computers that are good enough and big enough. It’s a prerequisite.

So chemistry and material science are sort of the sure bet, and optimization and machine learning are really hopeful. But it’s hard to pin down exactly when, how well they’re going to work, and how much impact they’re going to have. But I think everyone is very optimistic about those endeavors.

How do you see the convergence of AI, quantum, and HPC?

Quantum computers are good for specific classes of problems. If you have a problem that is not difficult for classical computers, it would be a ridiculously bad choice to run it on a quantum computer. I think you’re going to get much better results if you segment problems and distribute the calculation so that classical computing, AI, and quantum each do what they’re best at. We call this concept a quantum centric supercomputer – the idea is to use bits, neurons and qubits in the most efficacious way possible.

We actually recently announced a partnership with AMD to explore these ideas using their HPC hardware, our quantum hardware, and develop an open software stack to explore this landscape. One example is in chemistry simulation. There are large parts of chemicals that you can simulate very well classically. There tend to be relatively small sections of them where entanglement becomes very important, where possibly quantum computers may have a big impact.

One example is catalysis – the metallic sites inside of proteins. People believe this should be analyzed by a quantum computer. But if it’s something bigger, you’d want to do it with a classical computer because it’s faster and cheaper. Similarly, we use the quantum computer to pick the basis – the representation of the chemistry problem. And then we use the classical computer to actually solve it, because the classical computer has effectively a zero error rate and will give the exact right answer at the end. So we get the best of both worlds.

So we’re exploring these hybrid models in very concrete ways. We work with the University of Tokyo and RIKEN, where one of our quantum computers is paired with Fugaku. We also have a system at RPI working with their supercomputer AiMOS.

There are a lot of theoretical problems yet to be solved, for example, P versus NP. Do you think quantum computing will be able to solve such problems?

It’s funny that you mention P versus NP, because a large part of the birth of quantum information science has been extending that polynomial hierarchy into what it implies for quantum computers. There are new complexity classes that are specific to quantum computers that don’t appear in classical computers. And so practically demonstrating that you can take advantage of these complexity classes is huge.

That’s why the scientific question of quantum advantage is so interesting, because it’s saying we can take some of these other weird complexity classes and do things that aren’t Turing equivalent. Before that, a skeptic could argue you’re actually using a classical computer and faking a result. But when you have quantum advantage, you can see that these other complexity cases are there, outside of classical computers.

What will IBM Quantum be working on over the next few years?

Devices are going to continue to get better, bigger, better, faster. We usually talk about scale, quality and speed, number of qubits, error rates, and how quickly they can return the results to you. We’ll be working on these fault tolerant machines. They’re not going to be useful computationally for the next few years, because we’re working on small prototypes to get the technologies right. 2029 is the next big step with a large scale fault tolerant quantum computer. And we’ll continue to improve Qiskit, which we’ll base our products around. And we’ll continue to work on paradigms of computation like quantum centric supercomputing.

There’s intense competition, but there’s also a couple of milestones we’ve passed quietly.

When I entered this field, Step One was to build a quantum computer. You needed a physics lab and a semiconductor processing facility, and you needed to make it yourself. In 2016, that changed. IBM started making quantum devices available, and other people have followed suit. A lot of cloud providers now have quantum computational services. So we’ve managed to create an ecosystem where you can separate the people building quantum infrastructure from the people using it, which is part of solving that talent problem.

Then there was a lot of discussion around NISQ – Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum computing. The assumption was, if you have a small quantum computer, you’d inevitably get an inaccurate answer, and so you needed to find applications where getting an inexact answer was okay. That’s hard because most people use a computer to find the right answer. But in 2023, there were initial demonstrations that you could statistically get the right answer after the fact, provided you had a stable quantum computer – even if it’s small before fault tolerance.

That’s really a game changer, and it shows up in a ton of algorithmic research today. Algorithms that fall into this category include those for Sample-based quantum diagonalization (SQD), spin systems, and material science.

SQD, for example, changed how quantum computing has been perceived by chemists. Until then we talked about algorithms like the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), which was an old way of trying to do chemistry on quantum computing that people didn’t take seriously. And now we have people doing chemistry on quantum computers giving keynotes at chemistry conferences, because it’s really getting close to becoming a reality.

There’s a gathering excitement behind what we’re going to be able to accomplish over the next few years. We’re going to see claims of advantage. We’re going to see claims like HSBC’s, of people saying they’re getting value out of the computer.

Advantage is a scientific question. It really requires proof. Value is a much more malleable concept. There are a lot of ways you can find value. I remember arguing that putting the first IBM devices on the cloud was dumb; no one was ever going to use them because they were too small to be computationally useful. I was wrong. People wrote papers that got into peer reviewed journals. They did science with that device. And so although there wasn’t computational value, there was scientific value. Today, we’re really focused more on computational value. That’s why we have this fleet of very large, very performant devices. But value comes in many forms.